Earlier today my eldest son (7 years old) came up to me and asked me to help him buy Robux, the in-game credits for Roblox. He wasn’t asking me to pay for it — instead, he handed me $10 from his angbao savings and wanted to spend it on dressing up his Roblox avatar.

Obviously I said: “No.”

Later in the evening I was working on my old IBM laptop that is now around 16 years old. It runs Linux and I was using it to wipe some old hard drives I intended to dispose. While the slow wipe was running, I was bored and decided to play a retro game on my retro laptop: DOOM.

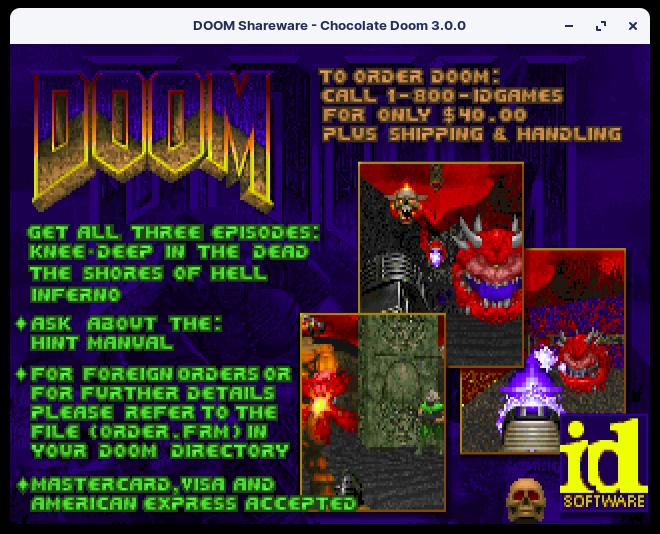

In the game, this help screen appears when you hit F1:

What caught my attention was that you could buy Doom for $40 (USD) including Shipping & Handling. $40 was quite a bit of money back in those days, but it was not just a game – Doom was one heck of an engineering feat for the price.

A little history — you can skip this part if you aren’t interested: Doom was developed back in 1993. When Doom was built, the game engine itself was entirely new and it was the first time the world has ever seen such real-time (pseudo-)3D graphics in a home computer. This was around the same time Intel launched the Pentium processor after its success with the 486. Let me repeat, in case it was not obvious: 66MHz was the fastest desktop CPU you could get at that time; your microwave oven probably has a faster CPU today. Games these days rely heavily on layers of technologies built over the years — hardware GPUs, 3D libraries/APIs (like DirectX/OpenGL), and game engines (like Unity). There were no such things back in 1993. Graphics in Doom is purely CPU-rendered.

But if I went to my parents back in 1993 and asked for $40 to buy the game, my parents would have gone:

“SIAO AH?”

This was what got me thinking: what was my son’s motivation behind paying for fancy clothes on his virtual character?

My generation today have accepted that it is normal to buy games. The transaction rewards the buyer with entertainment (playing the game), and the seller for their efforts (creating the game.)

30 years ago, my parents would have been paying for something that their parents (i.e. my grandparents) would have thought were simply a waste of money. 30 years from now, our kids will be paying for something that we thought was nuts today.

I was initially skeptical, but Mark Zukerberg may be up to something with this whole Metaverse thing. The technology is probably a bit too early for its time. Something must first exist to bridge the gap, and I think it might be in the form of an immersive, social-gaming app.

Another thing: There’s some misconception that the Metaverse is/needs Virtual Reality (VR); VR is one of many technologies that will enable us to live in the Metaverse, but it’s not the only technology. It is likely true that huge advancements in Virtual Reality (VR) or Augmented Reality (AR) technologies will enable more immersive and engaging metaverse experiences. The VR headsets we have today are akin to the PCs in the 1990s running pixelated 3D games: It looks crappy and uncomfortable to wear, and is sort of at the edge of getting better with graphics looking quite decent, but in due course the hardware size, performance and quality will likely catch up.

The fact though, is that some aspects of this Metaverse is already here. Think about where people are spending more time and money.

What does the future look like then?

Think about a world where the digital resources becomes even more convenient and easy to access; think about the walls of your homes simply made of large digital screens where you could do anything you wanted – meet a friend, go to work, pull up a photo; think about getting into a train but being in a virtual world where you could still talk to your kids at home… or on Mars?